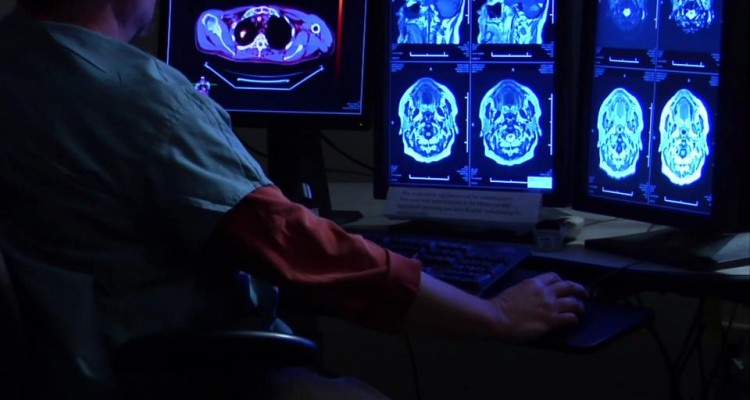

DelMar Pharmaceuticals is driven to fill gaps in care continuum.

DelMar Pharmaceuticals is developing drug candidates that target orphan cancer indications and represent market opportunities in the hundreds of millions of dollars in North America, and potentially billions of dollars worldwide. Its primary aim to develop products that will have both a high impact in patient care and a high return for investors.

An accelerated-timeline development model enables the company to use existing clinical and commercial data from myriad sources to reduce technical risk and support new regulatory filings with the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, Health Canada and the European Medicines Agency.

An orphan drug is a pharmaceutical agent that has been developed specifically to treat a rare medical condition, which itself is referred to as an orphan disease. It is often easier to get marketing approval for an orphan drug, and other incentives – such as extended periods of exclusivity – are provided to encourage the development of drugs that might otherwise lack a sufficient profit motive.

Orphan designations, too, have yielded breakthroughs that might not otherwise have been achieved.

“We’ve always been focused on moving something forward to solve an unmet medical need, and doing it in, hopefully, the most streamlined manner,” said Jeffrey Bacha, who co-founded DelMar with Dennis Brown and now serves as its chairman, president and chief executive officer. “There have been tremendous strides made in the treatment of cancer in the last 20 to 25 years, with the advent of targeted therapies, biologic therapies, antibody therapies. But they’re not perfect.

“And there tend to be gaps in the continuum of care.”

“And there tend to be gaps in the continuum of care.”

Given that reality, Bacha said, the concept behind the company was to go back and reconsider drugs that may not have been fully developed, but had shown documented efficacy in different tumor types and had been well-studied by an entity like the National Cancer Institute. That way, DelMar’s personnel could take something they knew was active and modernize their understanding of its biology and mechanics to the point where the drug might fill one of the gaps in the context of care.

“If so,” he said, “then we’re starting well down the field in terms of getting toward the goal line, because a lot of the animal work had been done, a lot of the toxicity work had been done, maybe Phase I clinical trials had been completed. And in many cases, some Phase II clinical work, so evidence of clinical activity in man against that type of cancer is already there.”

Ideally, that new-found knowledge would be quickly leveraged to a point where it could do something for patients and, in Bacha’s words, “unlock the value” of a compound that had been left on the shelf.

The business model emerged as an add-on to “Lipinski’s rule of five,” a process articulated in 1997 that served as a litmus test for evaluating whether a chemical compound with certain pharmacological/biological activity would be an orally active drug in humans. Brown took that set of rules and overlaid another set of screening criteria for cancer drugs, and, upon encountering existing compounds whose developments had been halted, discovered that many of them showed promise.

Ultimately, when the industry began veering away from traditional chemotherapies and toward antibody-based and targeted therapies, there were a handful of new substances available that answered Brown’s “What does a good cancer drug look like?” question – leaving only the biological and mechanistic research to do before the drug could be brought to market.

Brown used the process on several projects while serving as president at ChemGenix Pharmaceuticals until 2009, then re-joined with several former ChemGenix colleagues – after that company had been acquired by another entity – to create DelMar in 2011.

Synribo, now sold by Teva Pharmaceuticals,  became Brown’s first FDA-approved drug to treat chronic myelogenous leukemia in 2012, and DelMar is now hoping to repeat the success with VAL-083, which has received orphan drug designation in Europe and the U.S. for the treatment of gliomas and is approved in China for treatment of both chronic myelogenous leukemia and lung cancer.

became Brown’s first FDA-approved drug to treat chronic myelogenous leukemia in 2012, and DelMar is now hoping to repeat the success with VAL-083, which has received orphan drug designation in Europe and the U.S. for the treatment of gliomas and is approved in China for treatment of both chronic myelogenous leukemia and lung cancer.

“That creates a great opportunity for us,” Bacha said. “We believe we can address significant issues remaining in the treatment of glioblastoma with VAL-083, and potentially other cancers. But there’s also a pipeline of other assets that are sort of waiting in the wings, which we can access to begin to build our company as we go forward.”

DelMar began as a private Canada-based company, though it now maintains an administrative-only presence in Vancouver, B.C., while its research and clinical work is done out of Menlo Park, Calif.

The focus on orphan drugs not only brings with it the aforementioned opportunities for speedier regulatory approvals and market exclusivity, but will also require a smaller sales force and related infrastructure because of the comparatively low number of clinicians and medical centers treating the orphan diseases – which could make the company more attractive to potential outside investors.

Glioblastoma is the most common and aggressive primary brain tumor in humans, representing about 17 percent of all primary tumors. Median survival for adults on standard treatment is two to three years, though the timeframe dips to 14.6 months in more aggressive cases, where two-year survival is 30 percent. A 2009 study said almost 10 percent of patients may live five years or longer.

“We believe it is an attractive place to point investment dollars and believe that we can make a difference in terms of the quality of life and the survival of cancer patients with a relatively rare disease,” Bacha said. “The return on the investment, we believe, is very attractive.

“The ability to access the market is very attractive. And, of course, we wouldn’t be doing this unless we believed that this drug, with its clinical history and our understanding of the mechanism in a modern sense, can really solve a problem.”

AT A GLANCE

WHO: DelMar Pharmaceuticals

WHAT: Pharmaceutical company formed in 2010 to develop and commercialize proven cancer therapies in new orphan drug indications where patients are failing modern targeted or biologic treatments

WHERE: Administrative offices in Vancouver, B.C.; Research/clinical operations in Menlo Park, Calif.

WEBSITE: www.DelMarPharma.com